In Northern Spain, Agritourism Pushes Back Against Overtourism

This post was written by Sadie Bograd as a part of her O’Shaughnessy Global Food Fellowship.

I spent this past June living and volunteering on farms in Asturias, a rural coastal region of northern Spain. When I wasn’t repairing fences or harvesting beans, I was interviewing my hosts and neighboring farmers (and tour guides and baristas and bus drivers) about tourism. I had traveled to Spain hoping to understand how agritourism shaped small-scale farmers’ conception of their work and their community. Inspired by advertisements inviting tourists to “be a shepherd for a day” in Navarre or join a fishing crew in Galicia, I wondered: what happens to farmers when they shift from growing a product to selling an experience?

But when I arrived, I learned that the agrarian advertising belied a very different reality. Far from feeling overwhelmed by touristic interest in their work, the farmers I spoke to wished tourists cared more about their farms — wished they would do something other than complain about the smell of cow manure and the tractors blocking their photogenic views. The dominant model was not farm tourism, but rural tourism, in which visitors stayed in historic dwellings and visited natural landmarks but failed to engage with local communities. Agritourism, far from a challenge to farmers’ identities, had become a source of affirmation. It was a way to preserve traditions threatened by the arrival of mass tourism and a globalized culture.

What follows is a journalistic reflection on my time in Asturias. Endless thanks to Macarena, Gerard, Severino, Alejandro, Paula, Manolo, Arantza, and everyone else I spoke with for their candor and hospitality. I would also like to express my gratitude to the Yale Sustainable Food Program and the O’Shaughnessy–Global Food Fellowship for making this research possible.

* * *

Drive through the winding landscape of Asturias, a forested region on Spain’s northern coast, and you’ll see endless pastures of grazing sheep and cattle. You’ll pass by the jagged green-and-gray cliffs of the Picos of Europa, the crashing waves of the Bay of Biscay, the crystalline shimmer of the Lakes of Covadonga. You’ll encounter centuries-old stone churches and small wooden granaries, called hórreos, elevated on pillars to keep out rodents.

You will also see lots — and lots — of tourist rentals.

As climate change makes temperatures unbearable in Spain’s traditional tourist destinations, like Barcelona and the Mediterranean coast, both Spaniards and their European neighbors have increasingly fled northward. Each summer, thousands of domestic and international tourists spend weeks living in Asturian alojamientos rurales: traditional stone and wood buildings that have been converted into rentable lodgings in sparsely-populated villages. In 2019, an estimated 2.3 million people traveled to Asturias — a region with a population of just one million.

Travel writers hail Asturias as Spain’s “best-kept secret,” a region still unaffected by the kind of overtourism that has generated cost of living crises and widespread protests in cities like Barcelona and Seville.

But from the perspective of many locals, the tourist hordes are already here.

The Asturian government has been promoting the region as a “natural paradise” since 1985. But the new focus on Asturias as a “climate refuge,” combined with a post-pandemic surge in nature tourism, has pushed tourism rates to new highs. For Asturians, whose economy has long been based on ranching and farming, the arrival of so many visitors has brought with it countless challenges.

“You find people who come to the country but demand the standards of the city,” said Arantza Marcotegui, a local nature guide.

Visitors park their cars in front of farm gates. They complain about roosters crowing early in the morning and tractors blocking the photogenic view. They don’t want to smell any cow manure.

“If you’re in the middle of a village with cows, what do you want it to smell like?” Marcotegui exclaimed.

It’s not just the occasional rude behavior that has locals worried. The rural region’s infrastructure simply isn’t built to accommodate so many people, no matter how polite. Marcotegui claimed that some towns had to close their beaches last summer because of fecal contamination in the water, the result of so many people’s waste flowing into the river. Macarena Lapuerta, a yoga instructor who rents a room of her house to tourists, said that other villages don’t have enough water for laundry during the high season.

Even when the tourists go home, the prices stay elevated. Though tourism has brought economic benefits — in 2019, the tourism sector accounted for 12.71% of jobs and 10.6% of the economy — it has also led to a higher cost of living and an acute housing shortage. Many houses stay empty year-round so that tourists can rent them in July and August. This leaves local residents with no place to stay.

“If you want to be a teacher or a nurse here, there’s no housing. If you want to come work in tourism for the summer — they are always asking for waiters, but there’s no housing for them,”

Lapuerta explained. “There are more casa rurales [tourist rentals] than private homes, almost.”

The problem is exacerbated by increasing corporate ownership of tourist lodgings, according to Paula Valero Saez, a former deputy in Spain’s left-wing Podemos party and the owner of a local tourist house. While the economic benefits of tourism accrue to a smaller number of people and businesses, the costs are borne by the entire community.

As the economy shifts from agriculture to tourism, longtime residents also worry that their traditions will be lost.

“The tendency is to abandon, to forget the Asturian language and customs, to impose tastes and fashion from outside,” said Manolo Niembro, who runs a restaurant and leads food tours in the Asturian village of Asiego. He said people are learning English and French for work and failing to use the Asturian language. They are forgetting how to shepherd, to grow vegetables, to make cheese and cider — and losing the values of food sovereignty, patience, and environmental stewardship that accompanied those skills.

Asturias is known for its food: tourists eagerly seek out its cider, which is uniquely acidic and drunk in a single gulp, and fabada asturiana, a hearty stew of beans and pork sausage. Oviedo, the capital city, was named Spain’s Capital of Gastronomy in 2024, and the regional and national government have invested in a number of cider tourism initiatives. But according to some residents, even widespread gastrotourism has failed to support local farmers.

“The cider sector isn’t an agricultural sector, it’s an industrial sector,” said Severino García, founder of the Ecomuséu Ca l'Asturcón. Asturian families have grown their own apples (in farms called pumaradas) and fermented their own cider for generations. But the bottles tourists drink are often made in large factories and produced with apples from France or Czechia. The fabadas served in restaurants use beans from Peru or Bolivia.

Indeed, when I toured Sidra El Gaitero, a cidery in Villaviciosa, the guide focused far more on the company’s enormous machinery and successful export business than on the origins of its central ingredient. The promotional video they played showed a smattering of apple trees, but not a single farmer — in contrast to the dozens of shots of factory workers and processing plants. Cider was treated as an example of “industrial patrimony,” not agricultural heritage.

* * *

It wasn’t always this way. Some of the earliest tourism operators in Asturias saw tourism and agriculture as closely linked. Alejandro Rozalén Valero, Paula Valero’s son and the operator of the village house La Valleja, explained that some of the earliest rural lodgings — like the one his parents started — were tied to the incipient organic agriculture movement. His parents moved to Asturias in the 1980s, part of a wave of urbanites fleeing an economic crisis and seeking to return to the land. They opened the village house in 1997 after a decade of ranching goats and selling marmalade. Tourism created a new market for their agricultural products, which they could serve or sell to guests. García, of the Ecomuséu, also started renting his quintana, or country house, in 1991 as a way to support his family’s ceramic and wool artisanship, as well as their ranch of autochthonous species.

At the time, tourism seemed like a way to counteract rural depopulation. When Valero arrived in the small village of Rieña, the houses were full of families who had been there for 200 years, farming the same way they had for generations — but for whom “leaving here was a success.” “When we came here, people thought we had to be terrorists, or drug traffickers, because it didn’t make sense that people from Madrid with careers would come here,” she said. “‘They’re fleeing something,’ they said.”

Her arrival also coincided with Spain’s 1986 entry into the European Economic Community, the predecessor to the European Union. The EEC promoted an industrial model of agriculture, with larger farms obeying stringent hygiene standards: rustproof steel, automatized operations, hundreds of cows. Asturian family farmers, who were used to raising cattle for family consumption and selling small amounts of dairy to the market, couldn’t keep up — further fueling an exodus from the countryside.

“They demanded large investments, and people who had only 10, 15 cows, it was impossible to meet the hygienic demands of Brussels if you didn’t have something more to complement it,” Valero explained.

Valero, who trained as a biologist, was part of a European team working on an ecodevelopment plan for eastern Asturias. They thought sustainable tourism might be one such complement that could generate new income for farmers: “a responsible tourism, that wants to know how one makes things, that wants to understand the countryside.” It would be a way to stabilize the population and sustain local traditions.

Many farmers started opening up rooms in their houses. Lapuerta told me about a friend from a historic farming family, whose parents moved him and his three siblings into one room so that they could rent the other to tourists.

But as tourism grew, the focus was more and more on housing, and less and less on the farming culture it was meant to support.

“At the beginning, the casas rurales were linked to maintaining two activities; that is, you worked as a rancher, you worked in the field, and you had the house,” Rozalén said. “And increasingly people are specializing more in only having the lodging and it’s more like a hotel, and the other part that combines the field and the lodgings has been disappearing.”

Different people have different explanations for this shift. Marcotegui pointed out that tourism is often less labor-intensive and more lucrative than ranching. Rozalén described how difficult it could be to manage both an agricultural and a tourism enterprise at the same time. And Valero described how frustrating regulations can be for farmers: “They make it so difficult with bureaucracy that in the end you say, ‘Why so many difficulties? I’m going to be a waiter and that’s it.’”

The difficulty in supplying agritourism services mirrored a lack in demand. Lapuerta’s partner Gerard Jaumandreu, who maintains a small organic farm, explained that most tourists come to Asturias for three things: to see the Lakes of Covadonga, to ride a canoe down the River Sella, and to eat well. Understanding where fabadas and cider originated, or why their country farmhouse comes with an elevated granary, or how centuries of ranching shaped the pastoral landscape, isn’t part of the picture.

Public funding and regulations supported the transition from agritourism to a more generic “rural tourism.” National and international initiatives prioritized “economic criteria and increasing the supply of rural tourism facilities,” and deemphasized how tourists would engage with the rural environment outside their doors.

“The government sold the model of taking out the rural and putting in tourists,” García said. “An old house that had cows, take out the cows and put in Madrileños.”

As a result of all these forces, the Asturian population swells dramatically in the summer. But failing to support the longstanding local economy, tourism leaves shrinking communities behind in the fall. The region’s population has been declining since the 1980s, and a growing share is concentrated in cities like Oviedo and Gijón. According to Rozalén, many villages are “practically ghost towns” — including his own village of Rieña, where only three people live year-round.

“I would have liked it if tourism had served to stabilize the population,” Valero elaborated. “But since the tourism isn’t linked with the land, we’re losing many traditional activities like ranching and agriculture.”

* * *

The agritourism operators that remain see themselves as pushing back against this newly dominant model of disengaged rural tourism. They promote a revaluation of rural culture, of customs and values that now seem out of date.

Manolo Niembro and his brother, whose family has lived in Asturias for generations, started running the Ruta'l Quesu y la Sidra in 1999. Their tour takes visitors to the family’s cheese cave, pumarada (apple orchard), and llagar (cider workshop), before ending with a shared meal.

“Like all the families here, going back many years, everyone had livestock and everyone practiced a form of self-sufficient agriculture,” Niembro said. “We were establishing a kind of tourism that wasn’t just coming to the countryside, but understanding the countryside, participating in some of its activities.”

Having studied geography in university, Niembro views his tour as a “geographic excursion” — a way to understand the people and practices that shaped the rural landscape. He hopes to expose visitors to a lifestyle that seems old, but that he sees as vital for a sustainable future.

“People tend to identify the countryside with the old, the self-sacrificing, with what is out of fashion,” he said. “They think rural people are people without culture… [The tour] brings them an agreeable surprise, because they don’t know that the countryside is so complex.”

Valero and Rozalén, too, hope to help visitors gain a deeper understanding of their surroundings. They offer marmalade and cheese-making workshops and invite tourists to help them with the apple harvest. This fall, they will launch an “edible forest” program, in which they will guide guests through the forest to collect ingredients for a group dinner.

Like Niembro, Valero sees these types of activities as promoting “rural pride” for both tourists and Asturian residents. Lots of people “come to the countryside and only see green,” she says. The ability to look at a forest and identify walnuts and loquats, or to understand the geologic forces shaping different rocks, or to farm in a way that supports biodiversity and ecological balance: these are all valuable and unique forms of rural cultural knowledge.

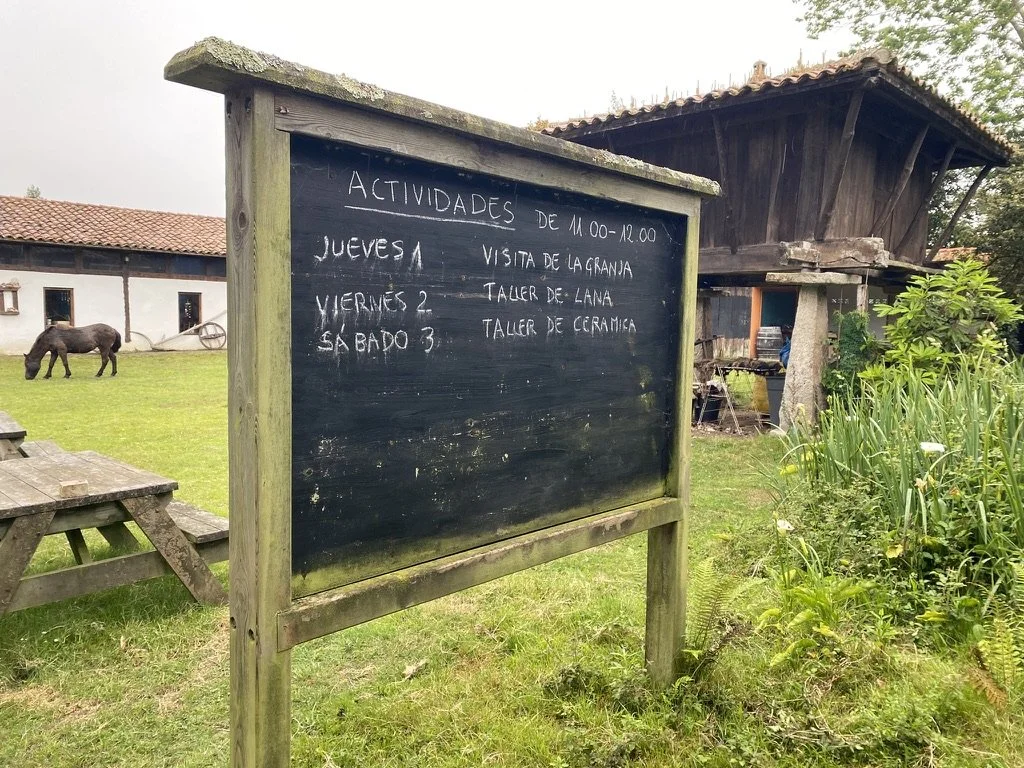

The goal is not to get rid of tourism, but to integrate it with rural heritage. García’s Ecomuséu Ca l'Asturcón runs ceramic and wool workshops, and leads guided tours through the family’s riverbank forests and pastures for native species. García described the Ecomuséu as “what Asturias should be: a balance between conservation and tourist activity.”

* * *

Even agritourism hosts, however, believe there is a limit to what agritourism can achieve.

Running a functioning farm while also guiding tours, leading workshops, and hosting guests is a lot of work. Niembro noted that the Ruta'l Quesu y la Sidra requires not just time and money, but emotional investment. He is unwilling to hire people from outside his family to impart a history that is not their own.

“This isn’t tourism you can delegate,” he said. “We tell the story ourselves.”

Rozalén said that sustainable and locally-connected tourism, because it is so labor-intensive, tends to be more expensive. Not many people are able to offer genuine agritourism, nor is everyone willing to pay for it. For both these reasons, there is a limit to how much these types of operations can grow.

To Niembro, that’s the whole point.

“Limited scale… is a very rural concept,” he said. Just as farmers learn to grow only as much as the land, and their labor, can sustain, he does not want his tours or his restaurant — or Asturias writ large — to accommodate more tourists than they can realistically support.

Most of the farmers I spoke with, then, think some kind of political intervention is necessary. There could be improved public funding for sustainable tourism. Rozalén said that complex permitting and other bureaucratic obligations make it difficult for farmers to access funding if they don’t have the money to hire a lawyer. He recommended that the state make a free online application to streamline police registries and other paperwork, since the existing services require payment. Niembro also suggested that government investment in agritourism needs to have a longer time horizon: after all, it takes 10 years for an apple tree to start bearing fruit.

But they also believe that the time has come to impose some limits. Valero said she thinks the government should add environmental and social criteria to their tourism policies. She also thinks the state should stop giving out permits to open tourist houses in congested areas.

“In the end tourism is very good, but it has to be quality tourism,” Rozalén said. “And sometimes, well, there isn’t enough quality tourism to feed all the tourists.”

Determining what limits on tourism is difficult. Asturias is one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever been, with its misty forests opening up into vertiginous cliffs and endless ocean. I understand why so many people want to visit. But if nothing more is done to protect the agricultural heritage that rural tourism is displacing, then the region risks losing what draws so many people in the first place.

“It’s hard for [tourists] to understand that this beautiful environment has to be maintained by someone,” said Marcotegui. “Most of this landscape wouldn’t be the way it is without ranchers. They shaped the landscape to be able to do what they do.”