Community-Based Food Justice Support in New Haven

This post was written by Meryl Braconnier as a part of her 2025 O’Shaughnessy Global Food Fellowship.

As soon as I parked the rusty van outside the senior center, it was game time—three hours of constant movement and flow, setting up the temporary farmstand for the eagerly awaiting customers. I focused on one motion at a time, in a chaotic dance with my two coworkers—open the trunk, set up the tents and tables, lug out the coolers upon coolers of vegetables, stack them high in rustic, wooden baskets, hang up our signs, turn on our pay station—all under the watchful gaze of dozens of elderly folks, with their walkers, canes, and wheelchairs, lined up against the dull beige bricks of the Bella Vista Senior Center. The front of the line had been waiting for nearly two hours, securing their primary selection of the local vegetables and fruit.

Residents at Bella Vista Senior Center lined up at the start of Common Ground’s Mobile Market on July 15, 2025. Photo Credit: Meryl Braconnier

Every Tuesday since mid-July, I’ve assisted with Common Ground’s Mobile Market—a farmstand on wheels that brings fresh, local, affordable produce directly to New Haven communities afflicted by food apartheid. Our diverse customer base contends with mobility, transportation, language, and financial challenges, on top of limited grocery stores, making it difficult, if not impossible, to access and afford local, nutrient-dense produce. The Mobile Market literally meets people where they live with cheaper, whole-sale prices, accepting federal benefits and offering 50% off purchases using the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), thanks to a matching donation from CitySeed, New Haven’s farmers markets organizer.

This summer, I furthered local food justice initiatives in New Haven, supported by the Yale Sustainable Food Program’s Global Food Fellowship and the Yale School of the Environment’s Carpenter, Leonard G. Fund. I split my time between Common Ground, an environmental justice charter high school, urban farm, and environmental education center, and Gather New Haven, the nonprofit that manages the city’s 40+ community gardens and offers community development programming.

During this practical, on-the-ground experience, I considered how to increase access and connection to healthy foods and nature through Common Ground’s Mobile Market and community gatherings. I also explored a new community engagement strategy with Gather New Haven’s garden network: the NYC Urban Field Station’s Stewardship Salons.

From Field to Feast: Increasing Food Access in New Haven

Through heat waves and rain, I assisted with all aspects of Common Ground’s vegetable production from planting to harvest and helped manage their Mobile Market outreach and delivery. Our farm team raked, shoveled, mulched, weeded, pruned, harvested, and sweated. Under our attentive care, our diverse crops, like kale, tomatoes, parsley, and beans, flourished on the 1-acre site. Urban growing spaces, like Common Ground’s farm and Gather’s community gardens, are largely constrained by size, soils, and resources. Their beauty and bounty radically resist our country’s cracked, inequitable systems of food production, distribution, and consumption, offering healing experiences and nourishment.

2025 farm intern team at Common Ground posing by freshly prepped beds for winter squash plantings. From left to right: Isabela, Linda, Pauline, Ethan, and Meryl. Photo Credit: Diane Litwin

With the Trump Administration’s devastating cuts and rollbacks in funding for environmental justice and food access programs, Common Ground was unable to hire a Mobile Market manager for the 2025 season. Thankfully, my coworker Ethan Reynolds and I received Yale funding to carry on with the Mobile Market’s 14th season.

Although our capacity was limited—dropping from the typical 5 stops per week to 1 stop per week—we held seven Mobile Market stops from June to August, split between the Bella Vista Senior Center, Cornell Scott Hill Health Center, and the Towers at Tower Lane, senior living community. At those seven, two-hour stops, we serviced nearly 350 customers. About 60% of our customers purchased their produce with federal benefits from the Farmers Market Nutrition Program (FMNP) for low-income seniors or for nutritionally at-risk women, infants, and children.

Myself and my coworker Takeira assisting a Tower 1 resident with her joyful kale purchase. Photo Credit: Karisma Quintas

All the fruits and vegetables sold at the Mobile Market are grown at Common Ground or on Connecticut farms within a 20-mile radius of New Haven. The Yale Farm donates crops when they have a larger harvest. The Mobile Market upholds a dignified dimension of food access work: ensuring people can eat healthy, high-quality foods that are relevant to their culture. I see the vital need for the Mobile Market in the long lines of customers waiting at nearly every stop and in the smiles on people’s faces when they share how they plan to prepare their fresh produce.

Stewardship Salons: Connection to Action to Resilience

In collaboration with Zion Jones, Gather’s Community Engagement Coordinator and Environmental Educator, and with the support of the NYC Urban Field Station, we developed and hosted six Stewardship Salons, facilitated by diverse community leaders, on the topics of safety on the urban farm, compost management, fermented DIY fertilizers, communal gardening values, local indigenous histories, and building sacred relationships with the land. Through my organization, creativity, and communication, I provided Gather New Haven with a transformative, community engagement model that helped them build connections to their communities and other social justice groups and facilitators.

Stewardship Salons are collaborative co-learning spaces where participants engage with place-based topics and exchange knowledge, building individual and collective capacity to care for natural resources, land, and communities (Stewardship Salon Guide, 2024). The Stewardship Salon framework emerged from a 2017 workshop titled “Learning from Place” hosted by Native Hawaiian master teacher, Kekuhi Kealiikanakaoleohaililani, bringing together Hawaiian and NYC stewardship practitioners. Since 2017, the NYC Urban Field Station (USDA Forest Service and NYC Parks Department) have hosted over 30 Stewardship Salons for the personal and professional development of their diverse stewardship practitioner network.

The workshops provided safe spaces for an open dialogue amongst gardeners, garden managers, and community members, catalyzing action through connection. Through our Safety on the Urban Farm salon, Gather staff and board members met Carmen Mendez of New Haven’s Livable Cities Initiative. Within a week of the salon, Mendez helped fulfill a priority safety measure for Ferry Street Farm in Fair Haven: installing flood lamps on the telephone poles looking over the growing space.

Gather's first Stewardship Salon, Saftey on the Urban Farm, at Ferry Street Farm in Fair Haven on July 9, 2025. Facilitated by Sadiann Ozment, a Gather NHV Board Member. Photo Credit: Meryl Braconnier

At our salon on Communal Gardening and Gather New Haven’s values hosted by Nadine Horton, founder and manager at the Armory Community Garden, we brought together 10 garden coordinators who oversee the volunteers and growing activities at Gather’s dispersed garden sites. This listening session provided a rare yet essential opportunity for the garden coordinators to get to know each other and share knowledge, fostering resilience between the urban growing spaces. One main outcome was the plan to create a shared communication channel, via Slack or Discord, for the garden coordinators to stay connected.

Following the salon, one of the participants emailed us with gratitude:

“Thank you all for organizing this salon with a joyous spirit and generous hospitality. [In my opinion,] it was much needed on so many levels:

· reinforcing/building relationships among garden leaders.

· having a say in the future focus and sustainability of this organization.

· visiting the lovely possibility of what could be as set by the Armory garden.”

Nadine Horton facilitating a conversation on communal gardening values with Gather's garden coordinators on July 19, 2025 at the Armory Community Garden. Photo credit: Meryl Braconnier.

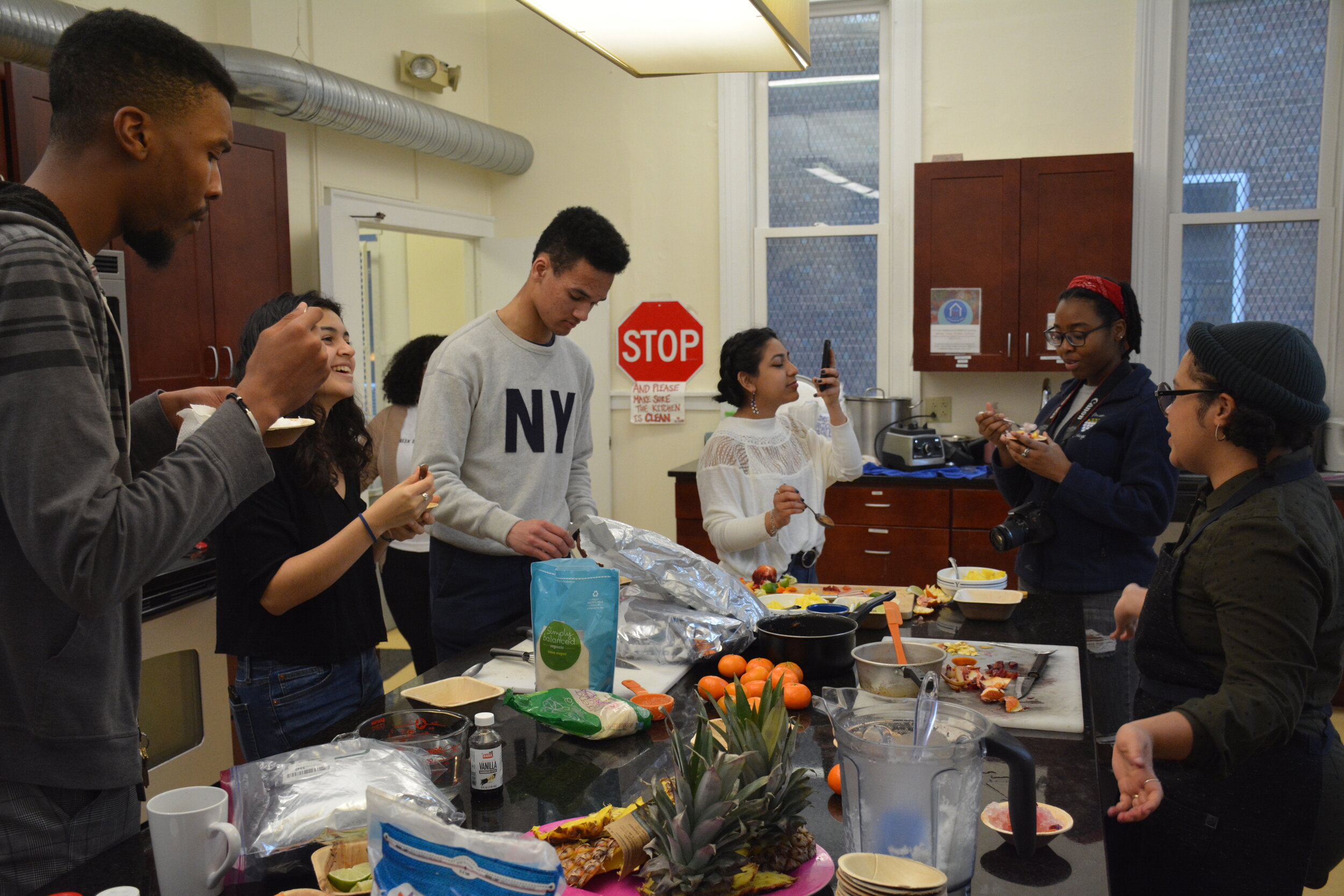

The Stewardship Salons on Compost Management and Korean Natural Farming (KNF) provided folks with the skills and knowledge to maintain their own garden spaces through regenerative practices. At the KNF Salon facilitated by Gather’s executive director, Jonathón Savage, 19 participants weeded Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris) from an overgrown garden bed, stripped the leaves into shared bowls, and massaged the fragrant leaves with brown sugar. Everyone took home some of the communal mixture, packed tight into glass jars covered with paper towels, to ferment into a low-cost, DIY plant amendment.

The final two workshops on Local Indigenous Histories and Building Sacred Relationships with the Land inspired deeper connections to place through historical context and meditative offerings of thanks to the earth. Guided by Clan Mother Shoran Waupatukuay Piper and Babalawo Enroue Onígbọ̀nná Halfkenny, I left small tokens of gratitude by the banks of the gurgling West River: lavender, tobacco, walnuts, and a slice of tomato.

As I gave my offerings, I lifted my gaze to meet the steady, glowing gaze of West Rock, illuminated by the setting sun. I thanked the cliff for watching over me this summer as I built relationships with Common Ground, Gather, community members, and the land, helping to feed my neighbors and build upon the deep, rich topsoil of community-driven, food justice initiatives in the Elm City.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the Yale Sustainable Food Program’s Global Food Fellowship and the Yale School of the Environment’s Carpenter, Leonard G. Fund for making my summer financially possible.

Thank you to the farm team at Common Ground, Deborah Greig, Diane Litwin, and Victoria Zucco. Thank you to Gather New Haven’s executive director, Jonathón Savage, to Zion Jones, and to the Farm Based Wellness Program coordinators, Ruth Torres and Celin.

Thank you to the Stewardship Salon facilitators, Sadiann Ozment, Nadine Horton, Takeira Bell, Jonathon Savage, Clan Mother Shoran Waupatukuay Piper, and Enroue Onígbọ̀nná Halfkenny.

Thank you to the NYC Urban Field Station team, especially Neha Savant and Lindsay Campbell, for your mentorship and guidance.