Hi’ilei Hobart, Indigenous Food Sovereignty (ER&M 316)

For students in ER&M 316, the class visit to the Farm was both instructive and restorative.

“So much of the story about Indigenous food comes out of these really difficult and challenging histories of settler colonial dispossession and erasure,” Professor Hobart said. “The Farm… gave students a lot of breathing space to build community with each other, to exhale just a little bit.”

“Teaching about the food system in a thoughtful way can feel a lot like doom and gloom,” she added. “So taking moments of actual joy becomes really important.”

The visits were also a form of “embodied practice” that helped students think about growing practices and labor in new ways. The class strung marigolds, tasted ciders, harvested crops, and assisted with Fall Feast, the annual celebration co-sponsored by the YSFP and the Native American Cultural Center.

Dr. Hobart spoke to the limitations on the Farm’s ability to promote Indigenous food sovereignty, given its small size, non-Indigenous leadership, and position within the institution of Yale. Still, she noted that practices like sourcing seeds from Indigenous seedkeepers, planting a Three Sisters garden, and growing plants in ways that honor their heritage can “really make a difference.”

More broadly, the Farm “gives space to allow people to come together thoughtfully [and] meaningfully,” she said. “Breaking bread together is not an uncomplicated process, but it so often does a lot to remind us that we are in community, even though that community can sometimes feel incohesive.”

Rachel Kauder Nalebuff, Reading and Writing the Modern Essay (ENGL 120)

As part of a unit on writing about place, Nalebuff takes each of her ENGL 120 sections to a distinctive spot on campus, like the YUAG or the Beinecke. Last fall, her students ventured farther north to the Old Acre for an exercise in “noticing what you notice.” They spent forty-five minutes sitting or wandering the Farm in silence, writing down whatever they observed.

“I really want to encourage my students to think about what it is that they can say about a place that no one else could say,” Nalebuff said. “Eventually you start to see things in new ways if you just spend enough time in a place.”

Nalebuff noted that the Yale Farm is a uniquely potent site for observation. “Being in any place, but maybe nature especially, often brings up personal memories,” she said. “A smell, or a certain kind of wind.” For students, the session on the Farm also formed an enjoyable experience that diverged from the pace of the indoor classroom. As she observed her students’ observations, Nalebuff felt that the class entered a “peaceful state” instead of having to “push through boredom.”

“It was such a spirited class, and everyone was grateful to be there and was so present,” she said. “It was one of those moments where the lessons of writing and of leading an engaged life felt so intertwined.”

Linda Puth, Plants and People (E&EB 145) and The Ecology of Food (E&EB 035)

Dr. Puth specializes in interdisciplinary science classes that are accessible without prerequisites. Her courses “highlight some of the strengths of the Yale campus that a lot of students never know are there until their senior year” — a list on which the Yale Farm is at the top.

Visits to the Farm bring Puth’s lectures to life. For example, the Farm’s wheat field showcases how plants evolve with domestication. Wild wheat has a center stalk that breaks apart when the grains are mature, dispersing the seeds widely so they don’t compete with the parent plant. But agricultural varieties evolved so that the stalk wouldn’t shatter, making them easier to harvest.

The class visits also explore nutrient cycling, pest control, and different systems of agriculture.

Puth is currently on leave to lecture at Yale-NUS College. Although the classes she teaches there are similar in theme, she has adapted the content to Singapore’s tropical location.

“Some of the students here have never been outside of the tropics and so they are used to constant day length — in Singapore, the day length changes by about 10 minutes per day over the entire year,” Puth said. “There’s never a freezing time. The seasonality is mainly just rainfall. So it's a very different system here and being able to talk about seasonal agriculture is a wonderful contrast.”

Puth’s class has explored these contrasts through guest discussions with Farm Manager Jeremy Oldfield, as well as through site visits to in-ground, rooftop, and vertical farms in the area.

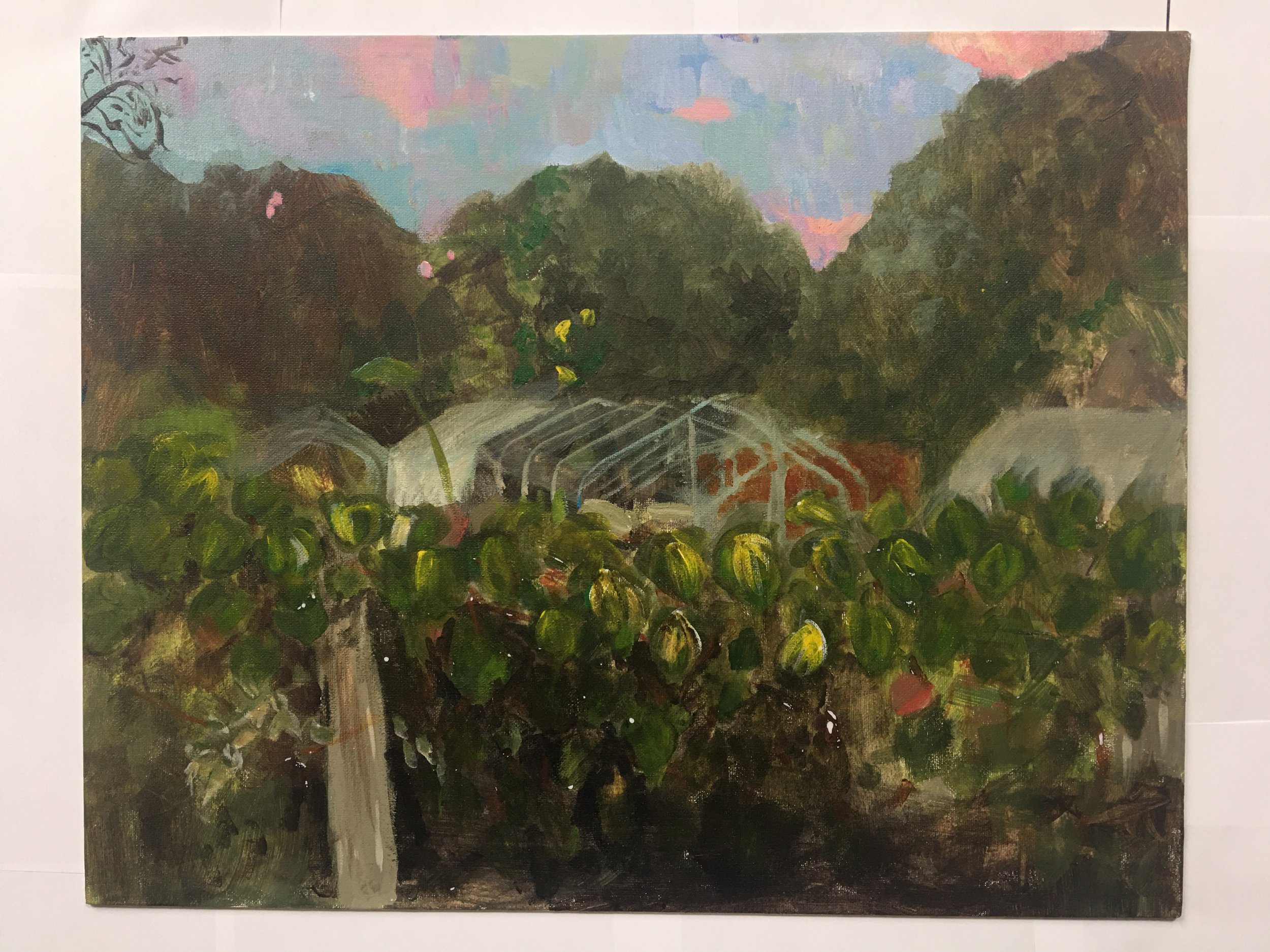

Sophy Naess, Painting Time (ART 332)

In a class about representing time in painting, there’s no better place to go than the Farm. ART 332 students make multiple trips to the Farm over the course of the semester, witnessing the Old Acre’s evolution over both a four-hour class and an entire season. The visits thus allow students to explore the passage of time on the small scale (like the changing light between late afternoon and early evening) and the large (like the growing and ripening of a field).

The class trips generate conversations about themes of pastoralism and labor, Naess said.

The Farm enables “thinking about the idea of nature as some kind of force to behold, as a romantic idea, versus thinking about the way that the space has to be constructed and cultivated,” she elaborated. “Conversations about that come up when talking about composition, framing. Are you representing the labor that happens here through looking at the wheelbarrow, or the shipping container that holds the tools?”

There are also countless opportunities to develop technical skills: working with figure and background, movement and abstraction, and above all, color.

The Farm is “so resplendent with color,” Naess said. “We really get into the myopic examination of the incredible range of color that exists within a small area of a garden.”

Max Chaoulideer, The Politics of Food (ENGL 114)

Chaoulideer’s writing seminar focused on many contentious topics in our contemporary food systems: urban agriculture, conscientious consumerism, the romanticization of agrarian life, contests over land usage and ownership. The class visit to the Yale Farm was a way to explore all of that.

According to Chaoulideer, Oldfield explained how the Old Acre is an “educational farm” more than an “agricultural” one. With its limited footprint, the Yale Farm will never produce enough to feed all of Yale’s campus. Instead, it serves as a space to “question or disrupt the status quo” through the crops it grows, the practices it employs, and the space it creates.

“A common throughline in the class was how to think about food both as a very concrete, practical, nutritional substance [and] as a kind of political tool,” Chaoulideer said. “For a lot of students, it was a new concept that… the place and process of growing could raise critical questions.”

The Farm became a reference for that kind of critical agriculture, Chaoulideer said. The YSFP is constantly exploring how it relates to Yale Dining, to the university as a whole, and to different parts of the New Haven community — “raising questions about what the Farm should be or could be.”

Many thanks to all these instructors for their time and generosity. This semester, new classrooms are coming to the Old Acre, including students from ENGL 114: Matters of Color / Color Matters, ARCH 1021: Architectural Design 3, ENG 114: What We Eat, and HSAR 553: Embodied Artisanal Knowledge.